Perineal trauma occurs in around 85% of births (McCandlish et al, 1998). Third and fourth degree tears, also known as obstetric anal sphincter injuries, occur in 2.9% of all vaginal births (Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists, 2015), and 6% of first vaginal births (Thiagamoorthy et al, 2014) in the UK. Some women may not experience symptoms after obstetric anal sphincter injuries, but up to 61% of women will experience anal incontinence, even after primary repair (Sultan and Thakar, 2007). Women with anal incontinence may experience emotional, social and psychological consequences, including embarrassment, isolation and a loss of dignity (Keighley et al, 2016).

As midwives assist with most vaginal births in the UK, they may be the only healthcare professional to examine a woman after birth. Therefore, training in the diagnosis of perineal trauma, including obstetric anal sphincter injuries, is essential. The Nursing and Midwifery Council's (NMC, 2019) standards of proficiency for midwives state that midwives must demonstrate, at qualification, the skill to ‘undertake repair of 1st and 2nd-degree perineal tears, and refer additional trauma’. Midwifery courses at UK universities vary in their content on perineal trauma, resulting in wide variation in training. There are some hands-on training courses in obstetric anal sphincter injuries available to midwives (Croydon Urogynaecology and Pelvic Floor Reconstruction Unit, 2023; Perineal Course, 2023), but they are not mandatory.

In 2007, a survey of two UK hospitals showed that more than 90% of midwives felt inadequately prepared to assess and/or repair perineal trauma (Mutema, 2007). Less than 40% of respondents in either hospital had attended any formal training in the repair of perineal tears (Mutema, 2007). A UK survey of midwives in 2021 (n=563) found that most midwives (99.5%) were confident in identifying first and second degree tears (Stride et al, 2021). However, they were less able to diagnose third and fourth degree tears (3a: 69.4%, 3b: 38.2%, 3c: 34.3%, 4: 60.7%) (Stride et al, 2021).

Education and training in obstetric anal sphincter injury diagnosis improve knowledge and confidence in practice. A significant increase (13.5%, P<0.001) in the diagnosis of obstetric anal sphincter injuries was demonstrated when women were re-examined by an experienced research fellow, after an initial examination by the midwife or doctor attending a birth (Andrews et al, 2006). Studies have shown that after education and training, there is an improvement in the diagnosis of obstetric anal sphincter injuries (Krissi et al, 2016; Ali-Masri et al, 2018). This was attributed to improved accuracy in the classification of trauma and awareness of risk factors and prevention techniques.

It is important that midwives have the knowledge and experience needed to diagnose obstetric anal sphincter injuries so that they can be appropriately referred and managed. In a study of failed primary repair of obstetric anal sphincter injuries, 23.5% of patients in the ‘failed primary repair group’ were in fact cases of obstetric anal sphincter injuries that were undiagnosed by midwives (Kirss et al, 2016). The aim of this study was to characterise midwives' current knowledge and training in obstetric perineal injuries in the UK.

Methods

This was a descriptive, cross-sectional study conducted in collaboration with a team in the USA. A revised version of a validated and published survey on experience and training in obstetric tears was used to collect data. The survey was originally created by Diko et al (2020; 2021) in the USA, which provided the potential to directly compare midwives working in the UK and USA. The survey was designed using Qualtrics, a secure online application for building and managing surveys.

Data collection

The Royal College of Midwives advertised and promoted the survey on Twitter and Facebook using a direct link. Reminders to complete the survey were sent on a monthly basis. The link was also advertised by a network of perineal midwives who work across the country. The survey was open for 4 months.

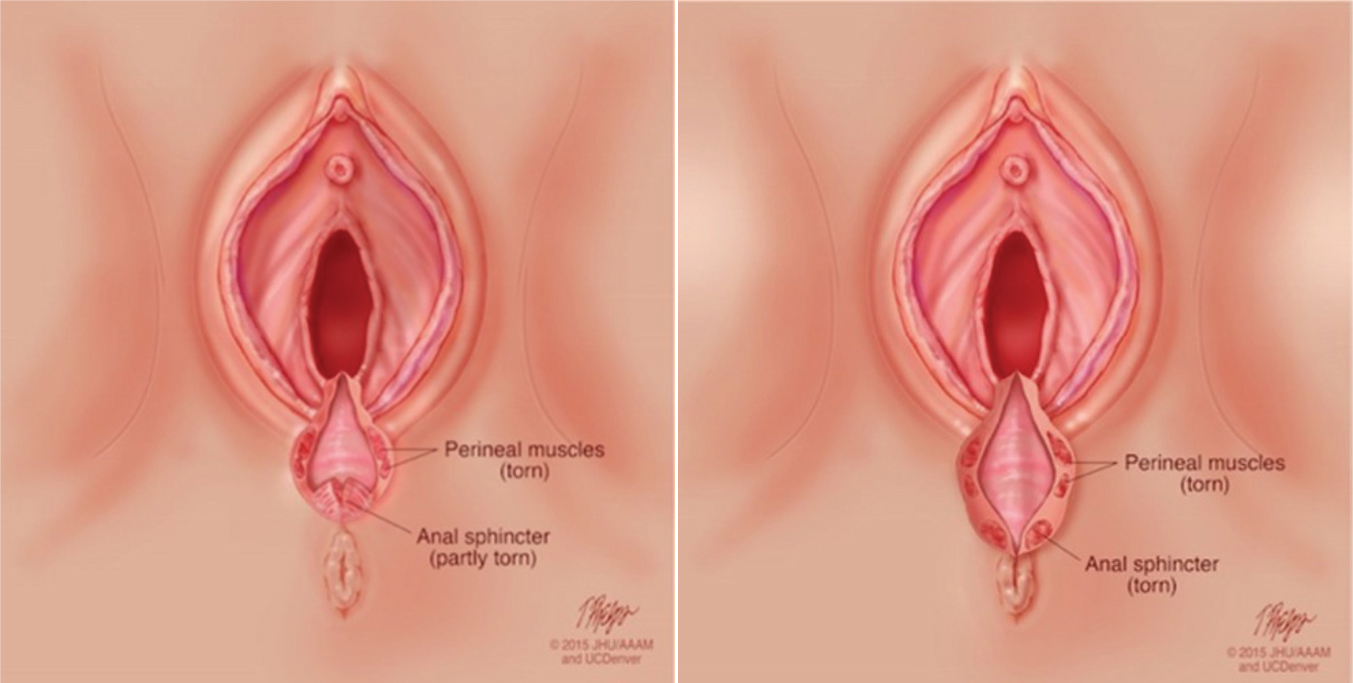

The survey had 58 questions regarding obstetric perineal trauma prevention, diagnosis, training and management. Nine images of perineal tears were included, drawn by a professional medical illustrator, which the participants were asked to classify (Figure 1). Participants were also asked to classify tears based on descriptive text.

The respondents who agreed to participate were working in the UK and had active participation in births (with an average of one birth/month in the last year). Survey responses were excluded if the participant was not currently performing clinical work in the UK, had not been involved in obstetric activities in the past year or the survey was incomplete.

Data analysis

The survey responses were collated anonymously in Qualtrics and analysed. For questions involving classifying tears (images and descriptive text), ‘correct’ responses were agreed on by the writers and correct responses were recorded as a score.

Factors associated with improved scores were analysed in two stages. Univariate comparisons between each factor and outcome score were assessed, followed by multivariable analysis. P<0.05 was set for significance. The checklist for reporting results of internet e-surveys tool was used for reporting the survey (Eysenbach, 2004).

Ethical considerations

The project was approved by the Health Research Authority (reference: 20/HRA/3309) and exempt from research ethics committee approval as it involved administration of a survey/interview procedures.

Results

A total of 149 midwives completed the survey.

Demographics

Table 1 shows the demographics of respondents, with 98.7% being female. The median number of years working, since university, was 7 years. The spread of participants around the UK showed 98.7% were working in England and 1.3% in Scotland. There were no respondents from Wales or Northern Ireland. The majority (65.1%) stated that their main practice setting was a hospital delivery suite.

Table 1. Participants' demographic and practice characteristics

| Characteristic | Category | Frequency, n=149 (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Job role | Band 5 preceptee | 8 (5.4) |

| Band 6 | 93 (62.4) | |

| Band 7 | 47 (31.5) | |

| Student | 1 (0.7) | |

| Age (years) | Median (range) | 34 (22–61) |

| Ethnicity | White/White British | 135 (90.6) |

| Asian/Asian British | 3 (2.0) | |

| Black/African/Caribbean/Black British | 3 (2.0) | |

| Mixed/multiple racial or ethnic groups | 5 (3.4) | |

| Any other | 2 (1.3) | |

| Prefer not to answer | 1 (0.7) | |

| Sex | Female | 147 (98.7) |

| Male | 2 (1.3) | |

| Years in practice | Median (range) | 7 (1–40) |

| Average number of births per month | Median (range) | 6 (1–50) |

| Current practice setting | Hospital delivery suite | 97 (65.1) |

| Birth centre | 24 (16.1) | |

| Community | 14 (9.4) | |

| Maternity wards | 9 (6.0) | |

| Antenatal clinic | 2 (1.3) | |

| Other | 3 (2.0) | |

| Geographic region | England | 147 (98.7) |

| Scotland | 2 (1.3) | |

| Wales | 0 (0.0) | |

| Northern Ireland | 0 (0.0) |

Training

Table 2 outlines participants' responses to questions about training. Only 50.3% of participants stated they had had training or continuing professional development in obstetric tears. However, 81.9% of all respondents stated that their training in obstetric tears was ‘adequate’, ‘good’ or ‘excellent’. Of those who had training, 89.3% received it within the last 5 years and 78.7% said their training had included obstetric anal sphincter injuries. The main reason for not undertaking training was ‘lack of courses’ (52.7%). When asked if they would be interested in obtaining more education or training in obstetric tears, 85.2% of midwives somewhat or strongly agreed.

Table 2. Training in obstetric tears

| Question | Response | Frequency, n=149 (%) |

|---|---|---|

| How would you describe your training on obstetric tears? | Very poor | 3 (2.0) |

| Poor | 20 (13.4) | |

| Adequate | 68 (45.6) | |

| Good | 48 (32.2) | |

| Excellent | 6 (4.0) | |

| Not received | 4 (2.7) | |

| Have you had continuous professional development or training on obstetric tears? | Yes | 75 (50.3) |

| No | 67 (45.0) | |

| Do not know | 7 (4.7) | |

| How many years ago was your last continuous professional development or training? | ≤5 | 67 (45.0) |

| 6–10 | 6 (4.0) | |

| Unanswered | 76 (51.0) | |

| In what learning environment was your last continuous professional development or training on obstetric tears? | Online | 12 (8.1) |

| In person | 52 (34.9) | |

| Multi-modal | 9 (6.0) | |

| Other | 2 (1.3) | |

| Unanswered | 74 (49.7) | |

| How long did it last (in whole hours)? | Median (range) | 2 (1–8) |

| What topics were covered in your training? | Obstetric anal sphincter injuries | 59 (39.6) |

| Episiotomy | 57 (38.3) | |

| Minor laceration repair | 45 (30.2) | |

| Complex laceration repair | 17 (11.4) | |

| Do not remember | 5 (3.4) | |

| Other | 1 (0.7) | |

| What is the main reason for not having training in obstetric tears? | Lack of time | 9 (12.2) |

| Lack of resources | 39 (52.7) | |

| Other (cost) | 1 (1.4) | |

| Do not know | 3 (4.1) | |

| Other | 21 (28.4) | |

| Are there local protocols/guidance readily available in your practice or hospital? | Yes | 116 (77.9) |

| No | 12 (8.1) | |

| Do not know | 21 (14.1) |

As shown in Table 3, very few participants described their ability to identify tears as ‘very poor’, but 10.1% described themselves as ‘poor’ at identifying third degree tears. Nearly half (45.6%) described themselves as ‘adequate’ at identifying third degree tears. When asked about the sub-category system to describe third degree tears, 89.3% of participants reported using it. Four midwives commented that they would expect a doctor to sub-categorise after reporting a third degree themselves. The majority of participants (77.9%) stated that there were available local guidelines on obstetric tears.

Table 3. Self-assessment of ability to identify obstetric tears

| Ability to identify tears | Frequency, n=149 (%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Very poor | Poor | Adequate | Good | Excellent | |

| First degree | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.7) | 12 (8.1) | 73 (49.0) | 63 (42.3) |

| Second degree | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 17 (11.4) | 74 (49.7) | 58 (38.9) |

| Third degree | 1 (0.7) | 15 (10.1) | 68 (45.6) | 61 (40.9) | 4 (2.7) |

| Fourth degree | 6 (4.0) | 22 (14.8) | 48 (32.2) | 58 (38.9) | 15 (10.1) |

Prevention

Table 4 shows the methods used by participants to help prevent obstetric anal sphincter injuries. The most commonly used methods were ‘controlled or guided delivery’ and ‘manual perineal support’. Warm compresses were used by more than half of midwives (69.8%). Almost all (91.9%) respondents performed episiotomies, with 136 using a mediolateral episiotomy and 1 using a median episiotomy. Over one in 10 (12.1%) of respondents reported that they avoided episiotomy, with 3.4% using a ‘hands off’ approach at birth.

Table 4. Methods of preventing obstetric anal sphincter injury

| Method | Frequency, n=149 (%) |

|---|---|

| Controlled or guided delivery | 139 (93.3) |

| Manual perineal support | 133 (89.3) |

| Changing birthing positions | 111 (74.5) |

| Warm compresses | 104 (69.8) |

| Perineal massage | 63 (42.3) |

| Physiologic pushing | 49 (32.9) |

| Delayed pushing | 28 (18.8) |

| Avoid episiotomy | 18 (12.1) |

| Avoid instrumentation with forceps | 16 (10.7) |

| Avoid instrumentation with vacuum | 14 (9.4) |

| Birth preparation instruments or devices | 8 (5.4) |

| Delivery between contractions | 6 (4.0) |

| Hands off delivery, no touching | 5 (3.4) |

| Routine episiotomy | 4 (2.7) |

| Other | 4 (2.7) |

| Dietary recommendations | 3 (2.0) |

| Selective episiotomy | 2 (1.3) |

| Avoid pool delivery | 1 (0.7) |

| Sex before birth | 1 (0.7) |

| None of the above | 0 (0.0) |

Diagnosis

Tables 5 and 6 show participants' identification of obstetric lacerations from standardised images and descriptive text. Participants were more accurate when identifying from images than from text. Almost all (98%) correctly identified a third degree tear with a partially torn anal sphincter, with 79.2% correctly identifying a completely torn anal sphincter as a third degree tear, while 20.1% thought this was a fourth degree tear and 1% were unsure. Over four-fifths of respondents correctly identified third degree tears from descriptive text. Identification of first and second degree tears and other perineal injuries was less consistent, with many respondents incorrectly using the Sultan classification for non-perineal injuries.

Table 5. Identification of obstetric lacerations from standard images

| Image | Answer, n=149 (%) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| First | Second | Third | Fourth | There is no tear | Do not know/unsure | Other/none of the above | Consensus | |

| First degree | 132 (88.6)* | 6 (4.0) | - | - | 5 (3.4) | 1 (0.7) | 5 (3.3%)† | First |

| Second degree | - | 140 (94.0)* | 9 (6.0) | - | - | - | - | Second |

| Third degree (partially torn sphincter) | - | - | 146 (98.0)* | 3 (2.0) | - | - | - | Third |

| Third degree (completely torn sphincter) | - | - | 118 (79.2)* | 30 (20.1) | - | 1 (0.7) | Third | |

| Fourth degree | - | - | 1 (0.7) | 148 (99.3)* | - | - | - | Fourth |

| Cervical | 4 (2.7) | 12 (8.1) | - | - | 6 (4.0) | 4 (2.7) | 123 (82.6)‡ | Cervical |

| Labial laceration | 25 (16.8) | 7 (4.7) | - | - | - | 2 (1.3) | 115 (77.2)§ | Labial |

| Periurethral | 50 (33.6) | 3 (2.0) | - | - | 3 (2.0) | 9 (6.0) | 84 (56.4)¶ | Periurethral |

| Vaginal sidewall | 16 (10.7) | 64 (43.0) | - | 1 (0.7) | 2 (1.3) | 3 (2.0) | 63 (42.3)** | Vaginal sidewall |

Other included vaginal tear (3), graze (2).

‡Other included cervical tear (122), labial tear (1).

§Other included: labial tear (115).

¶Other included: labial tear (45), vaginal tear (1), periurethral tear (28), clitoral tear (2) periclitoral tear (1), urethral tear (7).

**Other included: vaginal tear (63)

Table 6. Classification of obstetric lacerations from descriptive text

| Image | Answer, n=149 (%) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| First | Second | Third | Fourth | Other | Do not know | Consensus | |

| Only perineal skin torn | 138 (92.6)* | 2 (1.3) | 2 (1.3) | - | 6 (4.0) | 1 (0.7) | First |

| Only superficial posterior vaginal mucosa lacerated | 68 (45.6)* | 29 (19.5) | 1 (0.7) | - | 48 (32.2) | 3 (2.0) | First |

| Perineal tissue/muscles disrupted, external/internal anal sphincter and rectal mucosa intact | 1 (0.7) | 134 (89.9)* | 8 (5.4) | - | 2 (1.3) | 4 (2.7) | Second |

| External anal sphincter torn partially (<50% thickness) | 1 (0.7) | 8 (5.4) | 131 (87.9)* | 5 (3.4) | 2 (1.3) | 2 (1.3) | Third |

| External anal sphincter torn partially (>50% thickness) | - | 3 (2.0) | 128 (85.9)* | 13 (8.7) | 2 (1.3) | 3 (2.0) | Third |

| External anal sphincter torn fully, internal anal sphincter and rectal mucosa intact | 2 (1.3) | 10 (6.7) | 126 (84.6)* | 7 (4.7) | 1 (0.7) | 3 (2.0) | Third |

| External and internal anal sphincter and rectal mucosa torn | - | - | 12 (8.1) | 137 (91.9)* | - | - | Fourth |

| Vaginal sidewall laceration with intact perineum | 32 (21.5) | 41 (27.5) | - | - | 75 (50.3)* | 1 (0.7) | Other |

| Periurethral laceration with intact perineum | 26 (17.4) | 9 (6.0) | - | - | 107 (71.8) | 7 (4.7) | Other |

| Vaginal sulcal laceration (intact perineum) | 33 (22.1) | 24 (16.1) | - | 1 (0.7) | 69 (46.3) | 22 (14.8) | Other |

| Cervical laceration (intact perineum) | 3 (2.0) | 14 (9.4) | - | - | 126 (84.6) | 6 (4.0) | Other |

| Labial laceration (intact perineum) | 40 (26.8) | - | - | - | 108 (72.5) | 1 (0.7) | Other |

| External and internal anal sphincter intact, small high vaginal and rectal mucosa tear | 4 (2.7) | 27 (18.1) | 56 (37.6) | 22 (14.8) | 21 (14.1) | 19 (12.8) | Other |

Tables 7 and 8 outline the univariable and multivariable analyses of factors associated with score when identifying tears from images and text. In univariable analyses of all factors, only band and obstetric tears were significantly associated with score. In multivariable analysis, both higher band midwives (Band 7) (P=0.003) and those with training in obstetric tears (P=0.02) were significantly more likely to correctly identify and classify tears.

Table 7. Univariable associations with overall score

| Outcome | Category | n | Mean ± standard deviation | Coefficient (95% confidence interval) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Band | 7 | 47 | 78.8 ± 12.4 | 0 | 0.003 |

| 6 | 93 | 70.2 ± 15.0 | -8.6 (-13.6, -3.6) | ||

| 5/student | 9 | 69.1 ± 14.2 | -9.7 (-19.9, 0.5) | ||

| Age (for 10-year increase) | Continuous | 149 | - | 0.3 (-2.1, 2.8) | 0.80 |

| Age category (years) | ≤30 | 59 | 72.3 ± 15.5 | 0 | 0.92 |

| 31–45 | 65 | 72.9 ± 14.0 | 0.6 (-4.6, 5.8) | ||

| >45 | 25 | 73.7 ± 15.1 | 1.4 (-5.5, 8.4) | ||

| Sex | Female | 147 | 72.9 ± 14.7 | Insufficient data | - |

| Male | 2 | 65.0 ± 0.0 | |||

| Births/month | ≤10 | 113 | 71.7 ± 14.6 | 0 | 0.11 |

| >10 | 36 | 76.3 ± 14.7 | 4.5 (-1.0, 10.1) | ||

| Years in practice | ≤10 | 98 | 71.6 ± 15.0 | 0 | 0.18 |

| >10 | 51 | 75.0 ± 13.8 | 3.4 (-1.6, 8.4) | ||

| Self-assessment of training | Very poor/poor/none | 27 | 67.8 ± 14.6 | 0 | 0.12 |

| Adequate | 68 | 74.6 ± 15.0 | 6.8 (0.2, 13.3) | ||

| Good/excellent | 54 | 73.0 ± 14.0 | 5.2 (-1.6, 12.0) | ||

| Training in obstetric tears | No | 74 | 69.9 ± 15.3 | 0 | 0.02 |

| Yes | 75 | 75.6 ± 13.5 | 5.7 (1.0, 10.4) | ||

| Time of last training (years) (those who had training) | ≤2 | 45 | 75.2 ± 14.4 | 0 | 0.67 |

| >2 | 28 | 76.7 ± 12.4 | 1.4 (-5.1, 8.0) | ||

| Protocols available | No | 33 | 70.0 ± 16.5 | 0 | 0.21 |

| Yes | 116 | 73.6 ± 14.1 | 3.6 (-2.1, 9.3) | ||

| Involved in lawsuit | No | 148 | 72.9 ± 14.7 | Insufficient data | - |

| Yes | 1 | 61.0 ± 0.0 |

Table 8. Multivariable associations with overall score

| Outcome | Category | Coefficient (95% confidence interval) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Band | 7 | 0 | 0.003 |

| 6 | -8.5 (-13.5, -3.6) | ||

| 5/student | -8.0 (-18.1, 2.2) | ||

| Training in obstetric tears | No | 0 | 0.02 |

| Yes | 5.4 (0.8, 9.9) |

Management

When asked about postpartum care and repair of obstetric anal sphincter injuries, 80.5% of participants reported that they routinely performed a per rectal examination after every vaginal birth. None of the participants reported that they personally repaired any obstetric anal sphincter injuries (Table 9). One midwife had been involved in a lawsuit ensuing from an obstetric tear or complications.

Table 9. Other practices for birth and obstetric anal sphincter injury

| Question | Answer | Frequency, n=149 (%) |

|---|---|---|

| When do you typically perform a digital rectal exam after vaginal birth? | Routinely after every vaginal birth | 120 (80.5) |

| Only if perineum is torn | 25 (16.8) | |

| Only if perineum is torn deeply | 3 (2.0) | |

| After instrumental births | 0 (0.0) | |

| Other | 1 (0.7) | |

| Do you ever personally repair any obstetric anal sphincter injuries after vaginal birth? | Yes | 0 (0.0) |

| No | 149 (100.0) | |

| Do you ever perform episiotomies? | Yes | 137 (92.0) |

| No | 12 (8.0) | |

| What type of episiotomy do you typically perform? | Midline/median | 1 (0.7) |

| Mediolateral | 136 (91.3) | |

| No answer | 12 (8.0) |

Discussion

This small, convenience sample survey of UK midwives suggests that additional training is needed, especially for obstetric anal sphincter injury identification and diagnosis. Many (45%) midwives had no formal training in obstetric perineal trauma. Midwives with a higher banding and those who reported having training were more accurate at identifying and classifying obstetric perineal injuries. This may imply that training leads to improved knowledge in classifying perineal injuries.

It was encouraging that most midwives were able to classify tears from images and text. Although rates of training were low, this is not reflected in poor knowledge. When compared to midwives in the USA, midwives in the UK were better at classifying all types of third degree tears from images (USA: 66.3% and 86.7%; UK: 87.9% and 84.6%) and descriptive text (USA: 82.1%, 76.7% and 76.6%; UK: 87.9%, 85.9% and 84.6%) (Diko et al, 2021). This likely reflects the relatively more widely available education in obstetric anal sphincter injuries and perineal tears in the UK, compared to the USA, such as the obstetric anal sphincter injury care bundle (Jurczuk et al, 2021).

The participants' classification of third degree tears was better from images than text, which could imply that their visual recognition of anatomy was better than their understanding of anatomical terminology. Midwives in the UK are not required to repair obstetric anal sphincter injuries, but are required to recognise the presence of a third or fourth degree tear. However, they are required to repair first and second degree tears and a thorough understanding of anatomy is likely to improve recognition of obstetric anal sphincter injuries (Roper et al, 2020a). The Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (2015) recommends that all relevant healthcare professionals should attend hands-on training in perineal assessment and ensure that they maintain these skills.

When asked about their ability to classify tears, more participants rated their skills as lower quality for third and fourth degree tears compared to first and second degree tears. This was similar to findings in the USA (Diko et al, 2021). A UK survey in 2021 reported similar responses when participants were asked about their ability to classify tears, with more reporting they felt able to identify fourth degree than third degree tears (Stride et al, 2021). This implies the need for more training in obstetric anal sphincter injuries.

Obstetric tears that do not affect the perineum, such as periurethral and vaginal wall tears, are not included in the Sultan (1999) classification. In the present study, these were often categorised as first or second degree tears, similarly to midwives and physicians in the USA (Diko et al, 2021; Bunn et al, 2022). Tears may therefore be wrongly reported in patient notes, which can have implications for future births and national reporting of statistics. Wakefield et al (2021) suggested that electronic medical records may be more accurate when recording non-obstetric anal sphincter injury perineal tears, assuming the person entering the record has correctly identified the tear. A standardised nomenclature for non-perineal injuries could bring more clarity in how to describe these tears.

Accurate diagnosis of perineal trauma requires a per rectal examination to classify tears and ensure injuries such as rectal buttonhole tears are not missed (Roper et al, 2020a, b; 2022). It was reassuring that most (80.5%) UK midwives reported that they routinely performed a rectal examination after vaginal birth. However, further efforts are needed to encourage all midwives to adopt this practice. In the USA, only 13.6% of nurse-midwives routinely performed a rectal examination after birth (Diko et al, 2021), despite recommendations in national guidelines (American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, 2018). It is likely that the obstetric anal sphincter injuries care bundle (Jurczuk et al, 2021) in the UK is the reason for this success.

The bundle also promotes manual perineal protection for the prevention of obstetric anal sphincter injuries (Jurczuk et al, 2021). Most midwives in the present study reported that they used these techniques for birth, compared to the USA, where only 47.8% said they ‘support the perineum’ during birth (Diko et al, 2020).

Mediolateral episiotomy is reported to reduce the risk of obstetric anal sphincter injuries in certain clinical situations (Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists, 2015), which is also highlighted in the obstetric anal sphincter injury care bundle (Jurczuk et al, 2021). Most midwives in the present study reported that they performed episiotomies; however, in an earlier survey in the UK, only 40.7% of midwives had performed an episiotomy in the last 12 months (Stride et al, 2021). It is important for midwives to know when episiotomies are indicated and how to safely perform them. If they are not frequently performed, it is possible that midwives' confidence in performing the procedure may be affected. Improved training would increase confidence and performance.

Strengths and limitations

Aside from Stride et al (2021), which overlaps this subject, this is the largest UK national survey of midwives on obstetric anal sphincter injuries, which used a validated survey from other publications (Diko et al, 2020; 2021; Bunn et al, 2022). Only active clinicians were included in the study, which means the results represent current practice. Additionally, the survey assessed knowledge in two different ways, through images and text descriptions of tears, giving a greater representation of understanding.

However, there are some important limitations to this study. The number of respondents was small, and it is difficult to know the total number of midwives that the survey reached because social media was used to advertise it. The spread across the UK was also limited, likely because it was distributed from England. Given that the Nursing and Midwifery Council (2021) reported 24.7% of members were from ethnic minority backgrounds and the present survey had 90.6% white respondents, it may not be a good representation of the demographic.

The use of self-reporting, for practices such as prevention techniques, relies on honest and accurate answers from participants, who may experience recall bias, and the survey gives a snapshot of information at the time of conducting the survey. The clinical environment could not be matched by a computer survey, which means the diagnosis of tears cannot be truly tested by images and descriptions, but it does give an indication of knowledge and experience.

Conclusions

Many midwives reported that they had received no formal training on obstetric tears and would like more training. The authors recommend that a further study is conducted to investigate the availability of training in perineal trauma and obstetric anal sphincter injury for midwives in the UK. The authors also suggest that training for midwives in obstetric tears and episiotomy, including obstetric anal sphincter injuries, needs to be offered across the UK, with regular refreshers to maintain knowledge and confidence.

Key points

- This study surveyed UK midwives to assess their knowledge and training in obstetric anal sphincter tears.

- Half (50.3%) of respondents had received training in obstetric tears, with 85.2% reporting that they would like more training in this area.

- Midwives were better at classifying 3a tears than 3b tears.

- Those who had training and were a higher banding were better at identifying tears from images and descriptive text.

- Tha majority (80.5%) of respondents reported that they routinely performed a per rectal examination after vaginal birth.

CPD reflective questions

- Why is it important to perform a per rectal examination after every vaginal birth? How often do you do so?

- Have you received any training in obstetric tears? Would you have liked to receive further training in this area?

- Are you confident in your ability to identify and classify the different categories of obstetric tear?